Running Abaqus 2017 within a Singularity container (with hw-accel graphics)

When I started as a Research Software Engineer at the Uni of Sheffield a year ago I was given a lovely Dell XPS 9550 laptop to work on. The first thing I did was to install Arch Linux on it, which has so far proved to be extremely stable despite the rolling release model and the main Arch repository offering very recent versions of most FOSS packages.

Large engineering apps say no to bleeding edge Linux distros⌗

However, the one main issue with running Arch at work is that some commercial engineering software supports Linux but not all flavours: there are a fair few commercial packages that are only supported and only really work with RHEL/Centos/SLES and Ubuntu. Here’s what happens when you try to install the Abaqus 2017 engineering simulation software on Arch:

$ bsdtar xf ~/Downloads/Abaqus2017.iso -C ~/abaqus-iso

$ cd test/

$ ksh StartTUI.sh

CurrentMediaDir initial="."

CurrentMediaDir="/home/will/abaqus-iso/1/"

Current operating system: "Linux"

DSY_OS_Release="Arch"

Unknown linux release "Arch"

exit 8

Possible workarounds⌗

I’ve no issue with companies not wanting to support every flavour of Linux but I stubbornly want to continue running Arch on my machine so as I see it I’ve three choices:

- Hack the install scripts and create a rats nest of symlinks so the applications think they’re running on a supported flavour of Linux e.g. Centos;

- Run the applications unmodified on a supported Linux in a virtual machine;

- Run the applications unmodified on a supported Linux in a container.

I’ve opted for #3:

- 1 is ugly and brittle;

- 2 has associated performance and startup penalties as you’re emulating an entire machine in software.

Containery-whassits?⌗

Containers have been explained many times before in ways that I can’t aspire to. All I’ll say here is

- Containers provide operating-system-level virtualisation: they’re sandbox-like environments on (usually) a Linux machine.

- A container provides one or more types of isolation from the host operating system.

- E.g. the container typically has its own filesystem, providing in effect a tiny Linux virtual machine.

- But a containerisation technology may also have its own network interfaces/routes, users.

- This isolation allows you to do things like create container that runs one flavour of Linux and (usually) one application and for the container to be running on another flavour of Linux.

- Containerisation technologies are well-established and performant, in part as containers share a kernel with their hosts and there’s no emulation of bare metal.

- If you’re curious as to what makes this possible, read up on Linux namespaces and control groups (cgroups) which underpin all modern containerisation technologies such as Docker and Singularity.

The containerisation technology I used here is Singularity. You typically use it like so:

- Install the Singularity application

- Use this application to build an image which is a single file within which there is a semi-isolated version of Linux plus the application(s) that you want to run on that version of Linux e.g. in my case a Centos 7 install plus Abaqus 2017’s dependencies plus Abaqus 2017 itself.

- Use Singularity to instantiate a container from this image file and run something specific (Abaqus 2017) within it.

I say ‘semi-isolated’ as certain parts of the host are explicitly exposed to the container to make life simpler e.g.

- Home and temp directories;

- Networking config files: Singularity does not currently support network isolation so can use the system config files that list the active nameservers etc);

- Devices and device drivers, specifically NVIDIA graphics cards and drivers, a new feature which is useful for hardware accelerated graphics (e.g. of Abaqus’ GUI) but also for GPU computing (e.g. machine learning).

There’s quite a lot more to Singularity that I haven’t explained here; I recommend reading the excellent docs for a better overview and tutorials etc.

My first hardware-accelerated graphical app in a Singularity container⌗

Let’s see if we can run glxspheres64, a pretty graphical demo application, in a Centos 7 Singularity container from my Arch laptop.

After first installing Singularity (I’m using v2.4.2) we next need to build a Singularity image containing

the version of Linux we want to use inside our container plus the applications we want to run.

With Singularity, the cleanest way to build an image is from a definition file. For example, here’s my glxspheres.def definition file:

BootStrap: docker

From: centos:7

%post

wget -O /etc/yum.repos.d/VirtualGL.repo https://virtualgl.org/pmwiki/uploads/Downloads/VirtualGL.repo

rpm --import /etc/pki/rpm-gpg/RPM-GPG-KEY-CentOS-7

yum install -y VirtualGL glx-utils

yum clean all && rm -rf /var/cache/yum

%environment

#export PATH=xxx

%runscript

vglrun /opt/VirtualGL/bin/glxspheres64

%labels

Maintainer willfurnass

Version v0.1

We can then build a Singularity image file from this definition file using:

sudo singularity build glxspheres.img glxspheres.def

Let’s go explain the different parts of the definition file in turn:

- We first bootstrap the image (instantiate the filesystem) using a minimal Centos 7 image for the (competing) Docker containerisation system. There are other ways to bootstrap but this is probably the quickest. If we don’t already have this Centos 7 Docker image locally then it is downloaded from the Docker image repository.

- In the post section, we run certain build commands from within the container

(e.g. in this case on what seems to be Centos 7, not directly on the Arch Linux host).

Here we install the

VirtualGLandglx-utilspackages, which provide some prerequisites for running a hardware-accelerated graphical app in a container plusglxspheres64(in the VirtualGL package) and other graphical demo apps (inglx-utils). The third line in the post section removes unnecessary files to reduce the Singularity image size. - environment: we can optionally set the environment of the containers started from this image; I’m not bothering with that here.

- runscript: the default thing that is run when we start a container from this image.

We can run another program within the container when it starts if we explicitly specify the program.

vglrun, provided by VirtualGL, is necessary to run hardware-accelerated graphical apps within our container. - labels: image metadata.

You may be wondering whether you need to be a root-equivalent user to build a container. Yes, you do, as with Singularity you have the same user ID inside and outside the container and you need to be able to modify the root-owned parts of the filesystem inside the container.

We can then run glxspheres64 within our container with:

singularity run --nv glxspheres.img

Here we create a container that runs the default program in the associated image. From the perspective of this program it appears that it is running on Centos 7: pretty much everything in its local filesystems suggests that’s the case.

I should note:

- The

--nvflag tells Singularity to expose the host’s NVIDIA graphics device and driver to the container. This is a new feature that works pretty well. - On my laptop, I prefix

singularitywithoptirun, a tool on my machine that allows me to switch from using the on-board Intel graphics to my more power-hungry and powerful NVIDIA GeForce GTX 960M GPU. - As mentioned previously, directories like your home directory and

/tmpdirectory are ‘bind-mounted’ (made available) in the container by default. This is usually what you want.

When you run the container you should see something like:

If you terminate the main process in your container then the container will also exit.

Abaqus 2017 containerised⌗

Okay, on to doing something more useful: containerising Abaqus 2017 by building a Centos 7-based image.

My definition file, Abaqus config files (for automated installation) can be found in this repo,

as can a README file that explains most of the specifics; read that if you want the details.

One major difference between the Abaqus 2017 Singularity .def file and the one shown above is the Abaqus .def file contains a setup section that

runs various commands from the host’s perspective before the post section runs (which runs commands from the container’s perspective).

Here the setup section copies files needed during the image build from the host into the image.

As per the previous example, to get NVIDIA GPU accelerated graphics we need: the vglrun program (from the VirtualGL package) inside the container, Singularity’s --nv flag and in my case optirun (to select my NVIDIA graphics device).

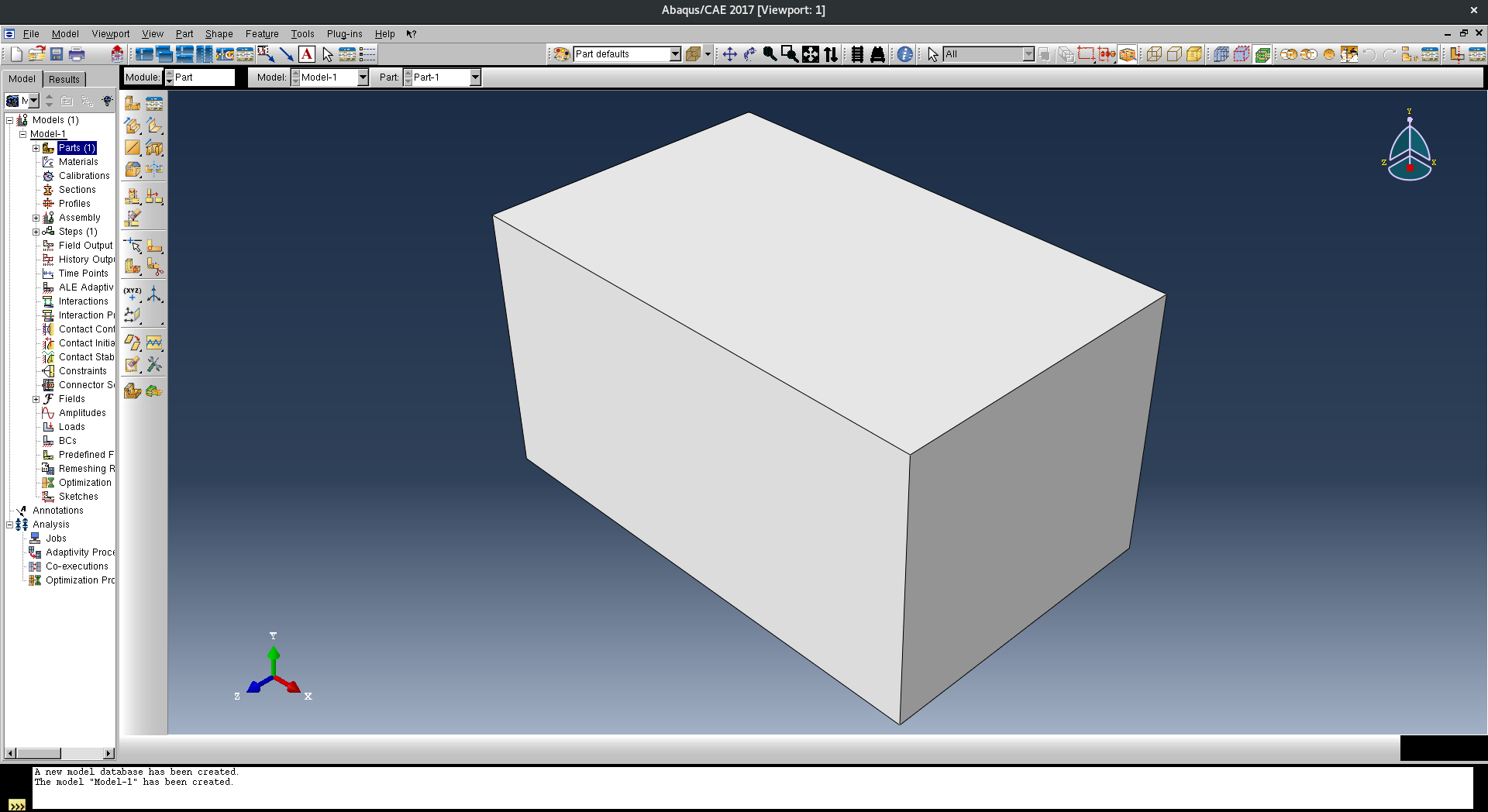

The end result (you’ll have to trust me here):

Portability⌗

You may be wondering what, if anything, prohibits you from copying the Singularity image to another machine with a new-ish version of Singularity installed and running it there?

Well, not much. You don’t need be a root-equivalent user to run a container, only to build one. The two main things you need to care about are that the license server is contactable at run-time from the new host, and secondly that copying the image may not be immediate as it’s not exactly small.

$ du -hs *img

11G abaqus-2017-centos-7.img

But thanks to Singularity using compressed squashfs filesystems within its images it’s about the same as size of a uncontainerised install of Abaqus 2017 (the Centos part of my image is pretty tiny compared to the Abaqus part).

Summary⌗

Singularity containers are great for isolating many types of applications and workflows.

Here I put a commercial graphical application in a container so it would think it was running on a different flavour of Linux than I have installed on my laptop, which it effectively is.

I can now move this container image around and could run it on local computer clusters or a cloud platform (so long as I can still talk to the application’s license server host);

this is made easy by the image just being a single file.

Also, I should note that the ability to use GPUs for graphics and computation from within containers is really neat, particularly now there is a standardised way of doing this with Singularity (the --nv flag).

There is much more I could write about Singularity but this post has already gotten a bit long so let’s call it a day.

If you have any comments or suggestions as to how this post could be improved then get in touch via Twitter.